https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/mobile/folders/16NtZEizC1tSyRNofstFAI504lx_I5Nco/1tRpt1X3NBNDiM5ultYJPFmyj81lJRQey?sort=13&direction=a

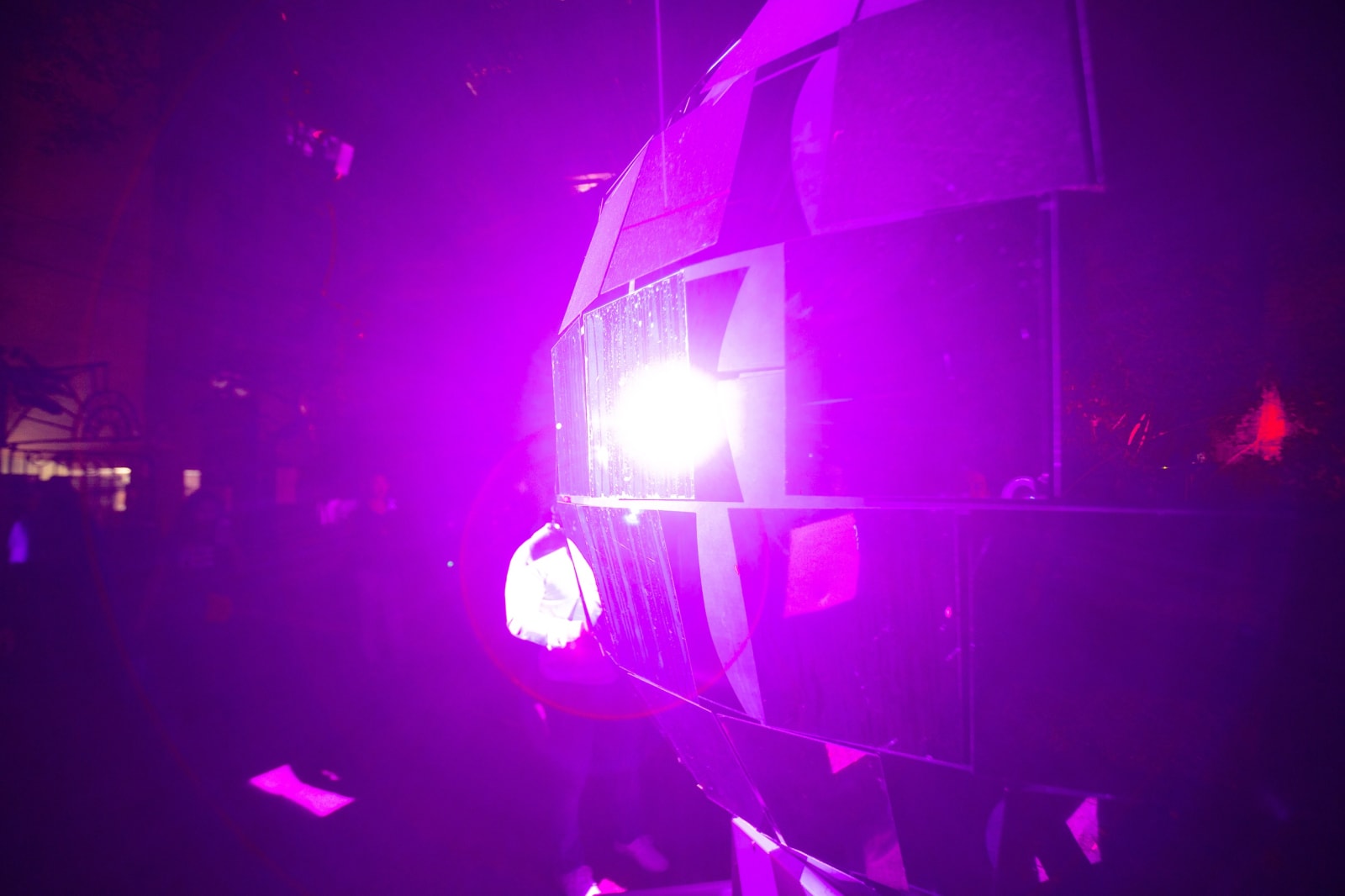

To Reflect Everything :: Toronto Sculpture Garden, 2023

Mirror Finished Steel, Painted Steel and Fiberglass

7' x 7' x 10'

Series: Public Artworks

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 16

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 17

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 18

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 19

)

Exhibition Text by Renata Azevedo Moreira Daring to place a 10 feet high version of a gleaming object that usually finds shelter in dark, enclosed, and loud spaces instead in...

Exhibition Text by Renata Azevedo Moreira

Daring to place a 10 feet high version of a gleaming object that usually finds shelter in dark, enclosed, and loud spaces instead in the outdoors can be disconcerting. Unwittingly encountering it while crossing a quiet garden on a sunny winter morning, when the white snowy ground appears to reflect all wavelengths of light that touch it, sounds almost like a joke. And yet Ryan Van Der Hout's To Reflect Everything unapologetically does it all, its expansiveness not to be confused with invasiveness. The sculpture is a hybrid of a disco ball and a space satellite, a radical attempt to queer simple definitions, functions, actions and values. It lives and shines and occupies space, its presence impossible to ignore – even if, sometimes, one may disappear inside its gaps.

When approaching the work, one might strive to find themselves, yet only come across their fragmented versions. Or would it be their multiplied versions? “To be a one at all, you must be a many and it's not a metaphor,” states feminist scholar Donna Haraway, pointing out that we exist always and exclusively in relation to each other and ourselves. This giant disco ball-satellite is a material refusal of anything's ability to only be one thing. It claims shape-shifting as the superpower of constantly becoming something else. It is a glittering manifestation of queer utopia.

To Reflect Everything consists of a silver steel base suggesting a cosmodrome, and a fibreglass spherical surface populated by dozens of polished mirrors irregularly distributed around it. The artist's main aesthetic inspiration is the satellite Ajisai, which has been orbiting the planet since its launch on August 13th, 1986. Thus, the work enacts queer desires to conquer freedom and acceptance here on Earth or in outer space, if need be. The multiple reflections reaffirm that bodies, be they human or anything else, are made of what surrounds them. This effort of multiplicity challenges binaries like self and other, private and public, what is hidden and what is shown.

Disco balls can reflect and refract not only physical imagery but also experiences, laughter, losses, and dreams. They introduce us to unknown avatars of ourselves, their light bouncing back and forth from whatever stands around them. This composite of mirrors confronts us with a multiverse of realities and storytellings, all versions of lives once lived or yet to live. It is a plurivocal screen with the capacity to capture the most unspeakable, wildest desires one may carry within.

In nightclubs, their usual habitat, it is believed that anything can happen. By transforming this familiar object into a spaceship and removing it from its shelter of carefree joy, Van Der Hout creates an embodied proof of Foucault's hypothesis that visibility is, indeed, a trap. That is true, of course, only if one believes their body's permeability can relate to an open space and to a hermetic sculpture at the same time. But by taking a step back, we can feel that this work is actually shouting, loud and clear, for everyone to be a part of it. The space of the disco ball literally is open to all – just “like a sparkling ocean,” says Black Studies scholar Jafari S. Allen.

So the invitation is made. Now you need to dare to accept it, and bring the party outside.

Daring to place a 10 feet high version of a gleaming object that usually finds shelter in dark, enclosed, and loud spaces instead in the outdoors can be disconcerting. Unwittingly encountering it while crossing a quiet garden on a sunny winter morning, when the white snowy ground appears to reflect all wavelengths of light that touch it, sounds almost like a joke. And yet Ryan Van Der Hout's To Reflect Everything unapologetically does it all, its expansiveness not to be confused with invasiveness. The sculpture is a hybrid of a disco ball and a space satellite, a radical attempt to queer simple definitions, functions, actions and values. It lives and shines and occupies space, its presence impossible to ignore – even if, sometimes, one may disappear inside its gaps.

When approaching the work, one might strive to find themselves, yet only come across their fragmented versions. Or would it be their multiplied versions? “To be a one at all, you must be a many and it's not a metaphor,” states feminist scholar Donna Haraway, pointing out that we exist always and exclusively in relation to each other and ourselves. This giant disco ball-satellite is a material refusal of anything's ability to only be one thing. It claims shape-shifting as the superpower of constantly becoming something else. It is a glittering manifestation of queer utopia.

To Reflect Everything consists of a silver steel base suggesting a cosmodrome, and a fibreglass spherical surface populated by dozens of polished mirrors irregularly distributed around it. The artist's main aesthetic inspiration is the satellite Ajisai, which has been orbiting the planet since its launch on August 13th, 1986. Thus, the work enacts queer desires to conquer freedom and acceptance here on Earth or in outer space, if need be. The multiple reflections reaffirm that bodies, be they human or anything else, are made of what surrounds them. This effort of multiplicity challenges binaries like self and other, private and public, what is hidden and what is shown.

Disco balls can reflect and refract not only physical imagery but also experiences, laughter, losses, and dreams. They introduce us to unknown avatars of ourselves, their light bouncing back and forth from whatever stands around them. This composite of mirrors confronts us with a multiverse of realities and storytellings, all versions of lives once lived or yet to live. It is a plurivocal screen with the capacity to capture the most unspeakable, wildest desires one may carry within.

In nightclubs, their usual habitat, it is believed that anything can happen. By transforming this familiar object into a spaceship and removing it from its shelter of carefree joy, Van Der Hout creates an embodied proof of Foucault's hypothesis that visibility is, indeed, a trap. That is true, of course, only if one believes their body's permeability can relate to an open space and to a hermetic sculpture at the same time. But by taking a step back, we can feel that this work is actually shouting, loud and clear, for everyone to be a part of it. The space of the disco ball literally is open to all – just “like a sparkling ocean,” says Black Studies scholar Jafari S. Allen.

So the invitation is made. Now you need to dare to accept it, and bring the party outside.

Exhibitions

2023 To Reflect Everything, Toronto Sculpture Garden and Nuit Blanche, Toronto, Canada

12

of

12